In the design review process for major national memorials in Washington—a process that almost always takes a decade or more—proposals are inevitably scrutinized for their compatibility with the two fundamental plans for the city, the L’Enfant plan of 1791 and the Senate Park (McMillan) Commission Plan of 1901. The design of the Dwight D. Eisenhower National Memorial by Frank Gehry has been criticized by many for violating the essential principles of these plans, principally for the impact of the monumental columns and tapestries within the axis of Maryland Avenue, which terminates on the dome of the U.S. Capitol.

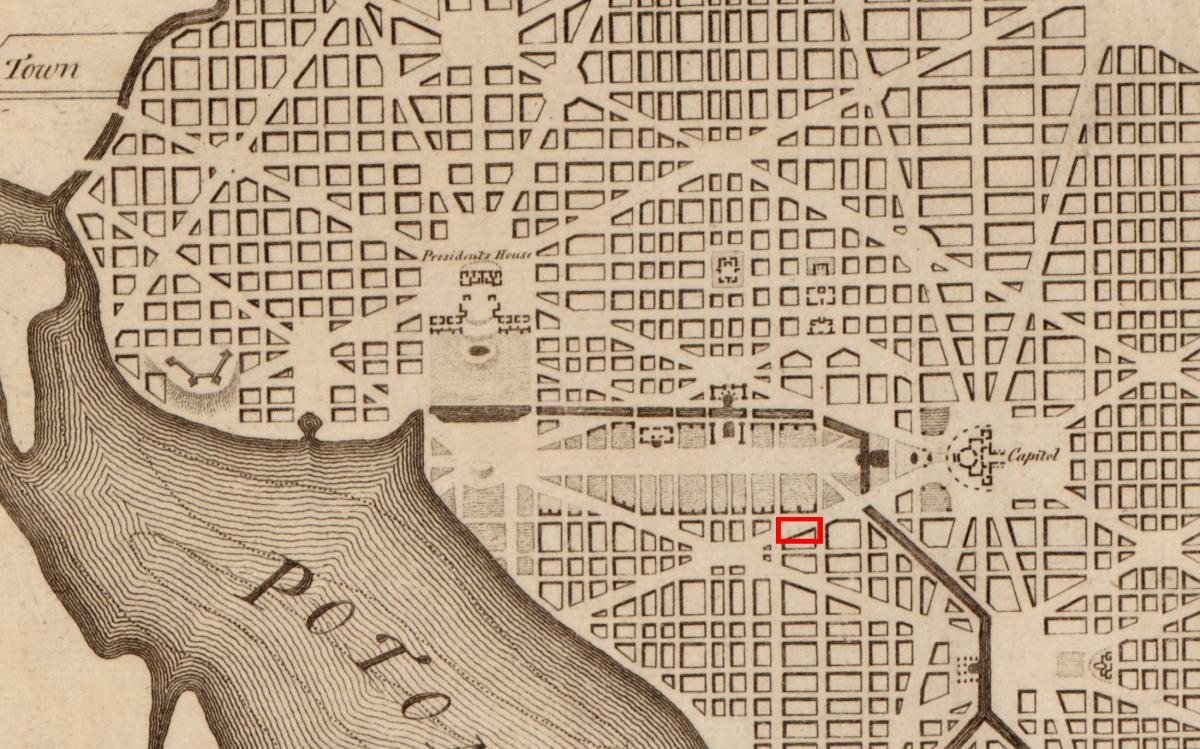

The Eisenhower Memorial site (outlined in red) in the L’Enfant Plan of 1791 is part open space, part building block. (Image credit: Library of Congress)

Likewise, the 1901 McMillan Plan design for the site presents the southeastern part of the site as a building edge defining a larger park system. (Image credit: CFA)

The reality of the Eisenhower Memorial site—a long rectangle between 3rd and 4th Streets along Independence Avenue, SW, and bisected by Maryland Avenue on the diagonal—is that it does not exist as a rectangular space on either of the historic plans. Both plans indicate a triangle of public space on what would be the northwest side of the Maryland Avenue; the southeastern side is considered city fabric—typically envisioned as buildings that define the edge of the avenue. Therefore, the issue is a question of how to apply historic planning principles to a modern condition within the city.

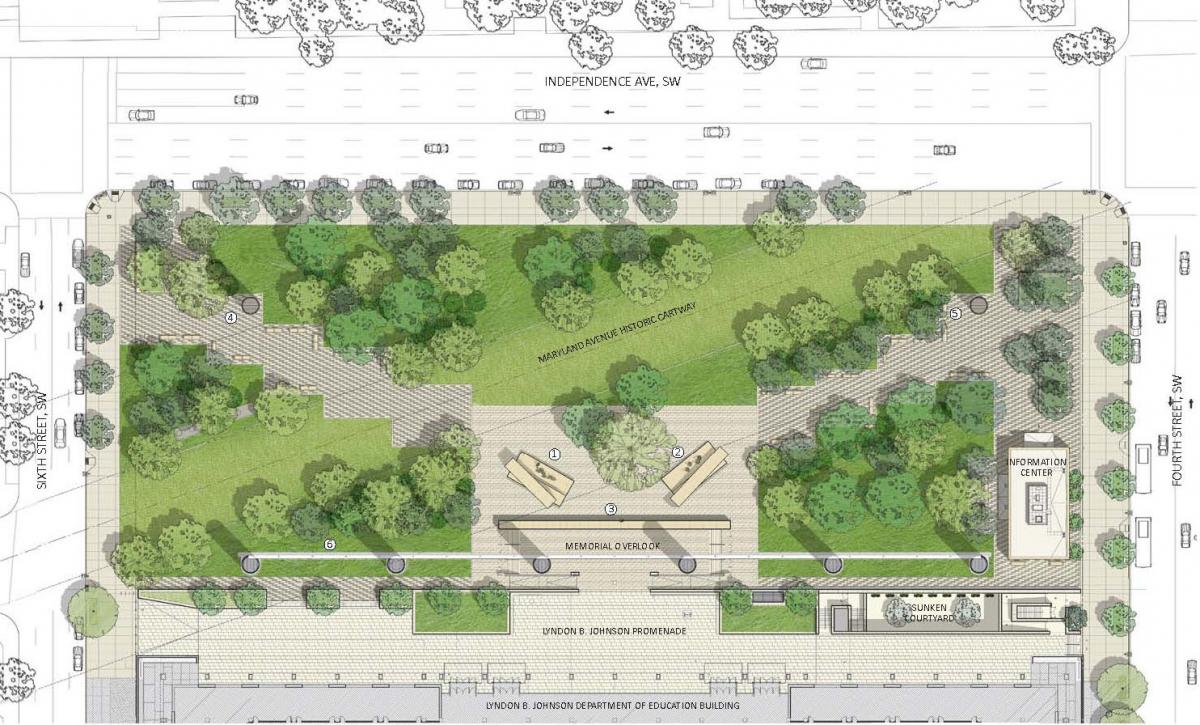

The memorial site is bisected by Maryland Avenue and would feature eight monumental columns, six of which support a stainless steel tapestry across the southern edge of the site. (Image credit: Eisenhower Memorial Commission)

The rectangular site for the memorial approved in 2006 reflects the legacy of mid-20th century development, where modernist design principles led to the construction of the Department of Education (Lyndon Baines Johnson) Building as an eight-story International-style bar across the south part of the block, leaving the adjoining triangle as a forecourt or plaza facing Maryland Avenue. The memorial site now encompasses most of this plaza, the Maryland Avenue right-of-way, and the historic public park in a single four-acre parcel.

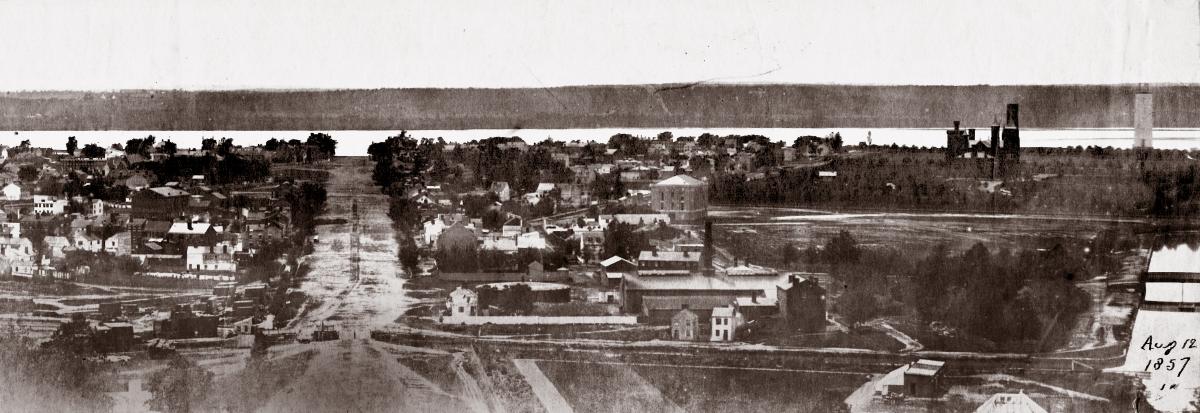

This photograph from 1857 shows Maryland Avenue as an open avenue defined by trees leading to the Potomac waterfront; the Smithsonian Castle and unfinished Washington Monument are at right. (Image credit: CFA)

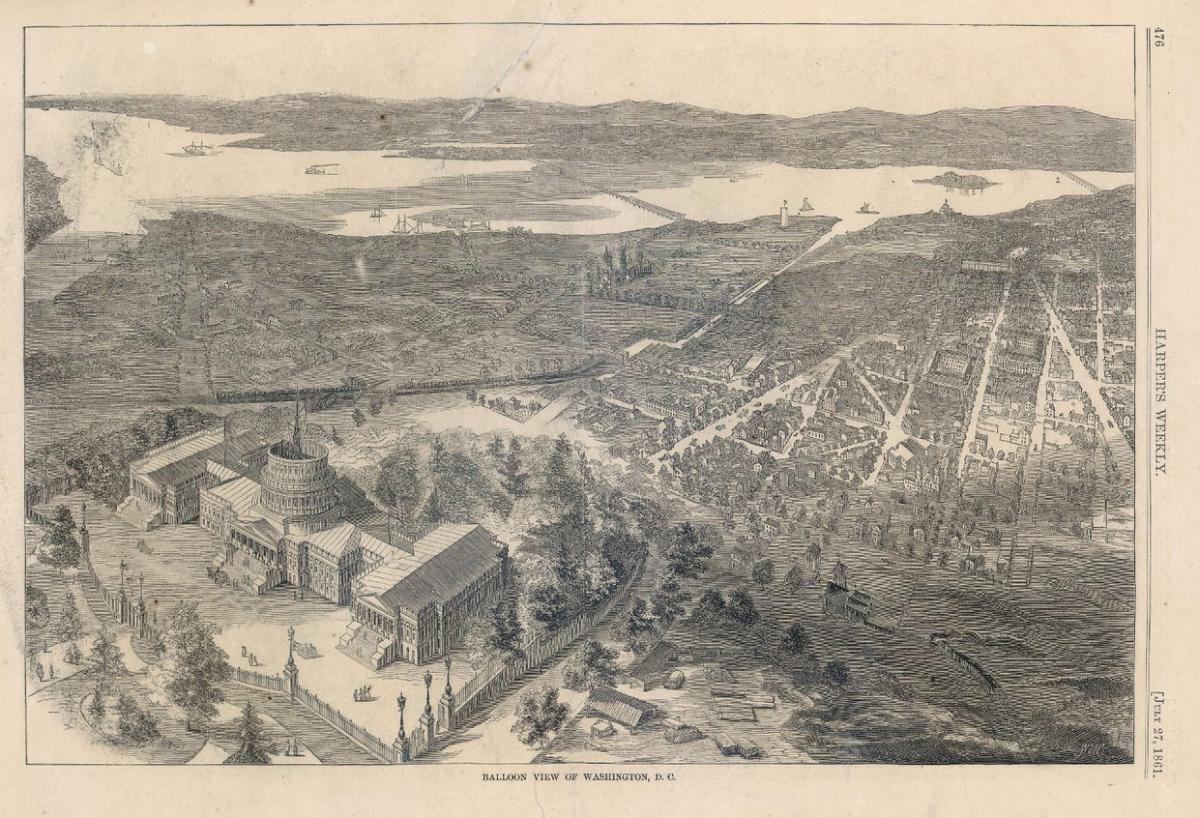

Maryland Avenue, SW, has a checkered history as the symmetric analogue of its more famous sister street, Pennsylvania Avenue, which makes a direct and symbolic connection between the seats of the executive and legislative branches—the White House and the Capitol. Historically, Maryland Avenue connected the Capitol to the major crossing of the Potomac River, eventually at what was known as the Long Bridge—now a series of bridges collectively referred to as the 14th Street Bridge—through a neighborhood that served the working wharves along the Washington Canal. By the mid-19th century, the B&O Railroad was located on part of Maryland Avenue, reinforcing that area’s industrial character and spoiling the avenue’s axial and functional role in the city plan. Mid-century urban redevelopment eventuated in the razing of the low-scale Southwest neighborhood and the construction of large government and private office buildings, many elevated thirty or more feet above the natural grade, and few of which worked to define the angled path of the historic avenue.

In 1861, Maryland Avenue—a swath depicted in this lithograph running from the unfinished dome of the Capitol to the Long Bridge in the distance—was much less developed than Pennsylvania Avenue, which is prominent as a diagonal on the right lined with buildings and full of traffic. (Image credit: The Philadelphia Print Shop, Ltd.)

In the past thirty years, planners and developers have worked to promote the worthy idea of restoring to whatever degree possible the Maryland Avenue corridor. The Portals development, planned in the late 1980s, sought to restore the avenue west of 12th Street, terminating in a circle surrounded by new development. NCPC’s 1997 Legacy plan and the 2009 CFA-NCPC Monumental Core Framework Plan also proposed building over the railroad corridor to recreate an urban avenue, but one punctuated by civic spaces: the historic Reservation 113 (at the latently symbolic crossing of Maryland and Virginia Avenues), the Portals terminus, and the consolidated public square proposed for the Eisenhower Memorial.

The insertion of the rail corridor and 20th-century urban renewal in the southwest sector has compromised Maryland Avenue and its relationship to the Capitol, seen here from the L’Enfant Promenade (10th Street). (Image credit: EDAW/AECOM for NCPC)

Which brings us back to the original question: Does the Eisenhower Memorial harm the city’s plan? Clearly, the interventions of the 19th and 20th centuries make the re-creation of a broad prospect from bridge to Capitol a virtual impossibility. The more salient question is how can such a significant axis in the city be treated now? A fundamental principle of the L’Enfant Plan was to treat major avenues as a commemorative framework for the city—a web of diagonals overlaid on a functional grid. Major intersections of these avenues were envisioned to feature public parks and squares that could honor worthy figures of importance to the nation. The grand avenues themselves, L’Enfant noted in his plan, “may be conveniently divided into footways, walks of trees, and a carriage way.”

The CFA-NCPC Monumental Core Framework Plan of 2009 envisioned the re-creation of the Maryland Avenue corridor decked above the existing railway infrastructure. (Image credit: EDAW/AECOM for NCPC)

Throughout the core of the city planned by L’Enfant this principle has been followed, with many circles and squares dedicated to political and military figures, usually featuring a commemorative statue or monument in the very center of that avenue’s axis. On Capitol Hill, public parks honor Seward, Stanton, Lincoln, Marion, and Garfield; on avenues radiating from White House, they honor Dupont, Farragut, Scott, Thomas, McPherson, and Logan. These civic spaces are fundamental to creating Washington, D.C.’s distinctive character.

Public commemoration is a typical treatment in Washington for significant public spaces marking the crossing of major avenues. In Logan Circle, a monument to Civil War general John A. Logan occupies the location where the axes of Rhode Island and Vermont Avenues intersect. (Image credit: Wikipedia)

Major monuments to presidents are no exception: in addition to the Washington Monument—which marks the central axes of the monumental core—the Jefferson Memorial terminates the 16th Street axis; the Lincoln Memorial terminates the axis of the National Mall; an equestrian statue of Washington occupies the intersection of Pennsylvania and New Hampshire Avenues. In honor of the president and general Ulysses S. Grant, a 250-foot-long composition of statuary sits at the foot of the Capitol Grounds, where Pennsylvania and Maryland Avenues begin to converge.

Memorials to U.S presidents in Washington are also often located on major urban axes. At left, an equestrian statue of General and President George Washington in Washington Circle, on the center axes of New Hampshire and Pennsylvania Avenue; at right, a monument to President James A. Garfield directly in the center of the Maryland Avenue axis. (Image credit: DCMemorials.com; National Park Service)

Sound familiar? The Eisenhower Memorial design has been criticized for introducing a monumental commemorative work honoring a U.S. president and military hero in the middle of an important axial avenue within the heart of the national capital. Even so, in the course of the design review process, the proposal has been modified to remove any vertical element from all but 32 feet on the south edge of the right-of-way, unless you count trees as intrusions. The trees themselves would be located to reframe the axis along the historic 90-foot-wide cartway, leaving what is a standard viewshed toward the Capitol at a width typical of any of the DC’s “grand avenues.” While Gehry’s design may not be a bronze general on horseback or a neoclassical temple, it is hard to argue that Washington’s planning principles are anything but reinforced by the proposed memorial.

The Gehry design for the memorial to Eisenhower, the U.S. president and Supreme Allied Commander in World War II, provides a 132-foot-wide frame for the Maryland Avenue vista toward the Capitol created by the monumental columns. (Image source: Eisenhower Memorial Commission)

1 Comment(s)

Sally Berk 19 June 2015